Screen Daily

By Silvia Wong

Published September 8, 2023

The Vietnamese film industry is celebrating its recent successes, from international accolades to local box-office record-breakers.

Ha Le Diem’s coming-of-age documentary Children Of The Mist made history as the first Vietnamese documentary feature to be shortlisted for an Oscar earlier this year. Pham Thien An won the coveted Camera d’Or at Cannes Film Festival with Inside The Yellow Cocoon Shell (see interview with the filmmakers, page 36), exactly 30 years after Vietnam-born French director Tran Anh Hung scooped the same prize with The Scent Of Green Papaya.

The first six months of 2023 saw a sharp increase in the local box office, clocking up 23 million admissions, comparable to the all-time high of 48 million recorded in 2019, pre-Covid. The estimated total revenue for the first seven months was $92.6m (vnd2.2tn), up 58.2% year-on-year.*

The surge was powered by two local megahits, which commanded a 38% market share between them. Comedy drama The House Of No Man, the solo directorial effort of actor Tran Thanh, made $19.3m (vnd458.6bn), dethroning 2021’s Dad, I’m Sorry, which Thanh co-directed, to become the highest-grossing film of all time in Vietnam, while Ly Hai’s action comedy Face Off 6: The Ticket Of Destiny took $11.5m (vnd272.8bn), making it the country’s fourth-highest grossing film to date.

The growth was also spurred by Vo Thanh Hoa’s action comedy Hustler Vs Scammer and Vu Ngoc Dang’s comedy drama Sister Sister 2, which both smashed the elite vnd100bn mark. Hollywood lagged behind, with Fast X the biggest import so far this year with $4.2m (vnd100bn).

“While many cinema markets have continued to suffer post-pandemic, Vietnam has seen a peak in record box-office sales this year,” says Victor Vu, the veteran director of Yellow Flowers On The Green Grass and Dreamy Eyes, both of which were submitted by Vietnam to the Oscars. “The most interesting fact is that the majority of box-office revenue has come from local Vietnamese films. There is a growing desire from the audience for relatable Vietnamese content.”

It was only two decades ago that Vietnamese authorities allowed the private sector to start making films. With a population of around 100 million, Vietnam’s box office had been growing by about 10% year-on-year from the mid-2010s, when the number of cinema screens surged due to investment by South Korean companies CJ ENM and Lotte Entertainment, and local chain Galaxy Cinema, which is backed partly by Golden Screen Cinemas’ Malaysian parent company PPB.

CJ and Lotte have been instrumental in getting the Vietnamese film market off the ground, having spent their first few years expanding the multiplex infrastructure before launching into local productions. CJ struck box-office gold with Phan Gia Nhat Linh’s Sweet 20 (2015) and Nguyen Quang Dung’s Go-Go Sisters (2018) — the two films were remakes of CJ’s popular Korean titles Miss Granny and Sunny, respectively. It has also formed joint venture CJ HK Entertainment with local production company HKFilm, which is behind The House Of No Man. Lotte also found success with its first production, Le-Van Kiet’s 2019 action film Furie, and Dung’s The Blood Moon Party, a local remake of Italian hit Perfect Strangers, amid the pandemic in 2020.

“Vietnam is now treading the same path that made Korea the powerhouse it became,” suggests Lotte Entertainment Vietnam director general Lee Jin Sung, a Korean executive based in Ho Chi Minh City. “What the Koreans learned has become an invaluable asset for Vietnam. Lotte and CJ were thus able to develop a mature value chain by introducing Korean investment, production and distribution systems to Vietnam.

“Vietnam will become the strongest content market in Southeast Asia within five years,” he predicts.

As the market heats up, Lee is aware that production costs will continue to rise, which may hamper future growth — but for now the bigger budget allows filmmakers to tackle diverse genres. Lotte is preparing releases of Vu’s The Last Wife, which is Vietnam’s biggest costume drama to date, and Timothy Linh Bui’s Daydreamers, the country’s first notable vampire feature (see Hot Projects, right). Sci-fi projects are also in development.

“Daydreamers is the first western-type vampire story produced in Vietnam,” says director Bui. “Many said it couldn’t be done due to cultural differences and censorship laws. But the timing is right as censorship eases restrictions on horror and certain subject matters.”

Legal hurdles

Censorship has long proved a sticking point, for both local and international titles, and Vietnam’s cinema law had been a major hurdle. Local films that earned international recognition — such as Bui Kim Quy’s The Inseminator, which played Busan and Rotterdam, and Le Bao’s Berlinale award-winning drama Taste — were not licensed for release. Tran Thanh Huy’s crime drama Rom, the first Vietnamese film to win Busan’s New Currents award, sparked heated debate before it was passed with edits, and Ash Mayfair’s The Third Wife, which premiered at Toronto in 2018, was pulled from local cinemas after a few days due to controversial sex scenes.

Local filmmakers have been pushing hard for more well-defined censorship regulations. After consulting the public and the Motion Picture Association, Vietnam finally moved away from an approach of pure censorship and adopted a rating system with clearer references, which came into effect earlier this year. The industry has broadly welcomed this significant step forward, but authorities still have the power to censor features.

Films that depict the nine-dash line — used on Chinese maps to show its claims over disputed areas in the South China Sea — always cause trouble. Warner Bros’ Barbie was the latest film banned for including the “offending image”, following the same fate as Sony’s Uncharted and DreamWorks animation Abominable. Netflix also removed Australian TV spy drama Pine Gap from the Vietnamese market following a complaint from authorities.

North American profile

Conversely, Vietnam has built strong links with the US. Many top directors such as Kiet, Victor Vu, Timothy Linh Bui, Charlie Nguyen (The Rebel) and Ham Tran (Maika) were either born or raised there and bring a different aesthetic to Vietnamese cinema. The US, which has the largest overseas diaspora, is a key international market for Vietnamese films.

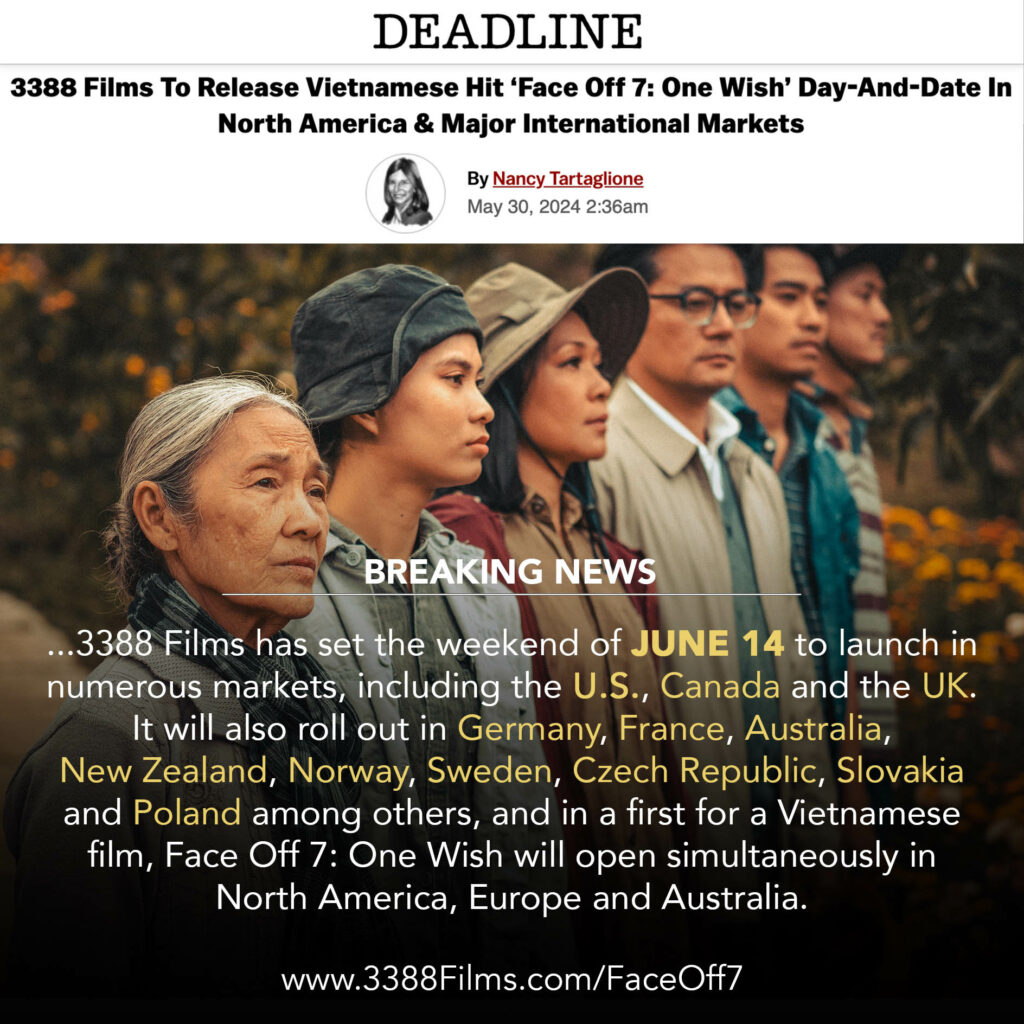

Dad, I’m Sorry became the first Vietnamese-produced title to surpass $1m at the US box office. “There would be perhaps one or two films [released in North America] every few years but we’re now seeing four to six films every year,” says Thien A Pham, founder of California-based distributor 3388 Films. “This clear uptrend is a positive indicator that there is still a lot of untapped market potential. After we released Dad, I’m Sorry on nearly 50 screens in 2021 — the most for a Vietnam-produced film up until then — the screen count has now become the norm and the number will only increase in North America.”

Nevertheless, Vietnam lacks a true breakout hit that can attract a wide international audience, not just the diaspora. Greater international exposure can be achieved if more Vietnamese films secure stronger government support and sales representation.

“The local industry receives little-to-no support from the government to participate in major markets, whereas many countries in the Asean region have spent years organising national pavilions and supporting their professionals to join key industry events,” says Jeremy Segay, the Hanoi-based regional audiovisual attaché for the Embassy of France.

To train Vietnamese film professionals, the French Embassy launched the Fast Track To Cannes Market programme in 2022. “Two young Vietnamese distribution or marketing executives are invited each year to have the full Cannes experience and see for themselves how international film promotion is conducted,” says Segay, who discovered many new Asian talents when working as a programmer for Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes in the 2000s.

Vietnam will certainly benefit from having more local executives with international distribution experience. While CJ and Lotte represent their own Vietnamese titles through their global sales teams, BHD and Skyline Media are among the few Vietnam-based sales outfits.

Foreign sales companies that handle Vietnamese titles include South Korea’s Finecut, which picked up Rom, and US-based EST Studios, which boarded Maika. US sales outfit WME Independent, which has a representative in Singapore, handles Kiet’s The Ancestral and Veronica Ngo’s Furies; the latter took the fourth spot on Netflix’s global non-English films list with 4.3 million views after a week on release. WME’s latest pickup from Vietnam is Dan Trong Tran’s action drama Bad Blood, which stars Kieu Minh Tuan (Jailbait) and opened locally on August 25.

The revised cinema law has also allowed provinces and cities to host their own film festivals, not just through the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism. Da Nang Asian Film Festival (Danaff), which took place in May, was the first such event organised regionally.

“This is in line with the trend of the global film industry,” says Ngo Phuong Lan, director of Danaff and chairwoman of the Vietnam Association of Film Promotion and Development, which functions as a film commission to cultivate international collaborations and attract footloose productions to film in Vietnam. “When a culturally rich city is connected with regional and international cinema, it will help bring local cinema to new heights and spread the charm of the beautiful locale.”

* Official box‑office statistics are not published in Vietnam — the figures in this article are provided by Box Office Vietnam and Lotte Vietnam